Read this before you pivot your startup

Mar 25, 2024

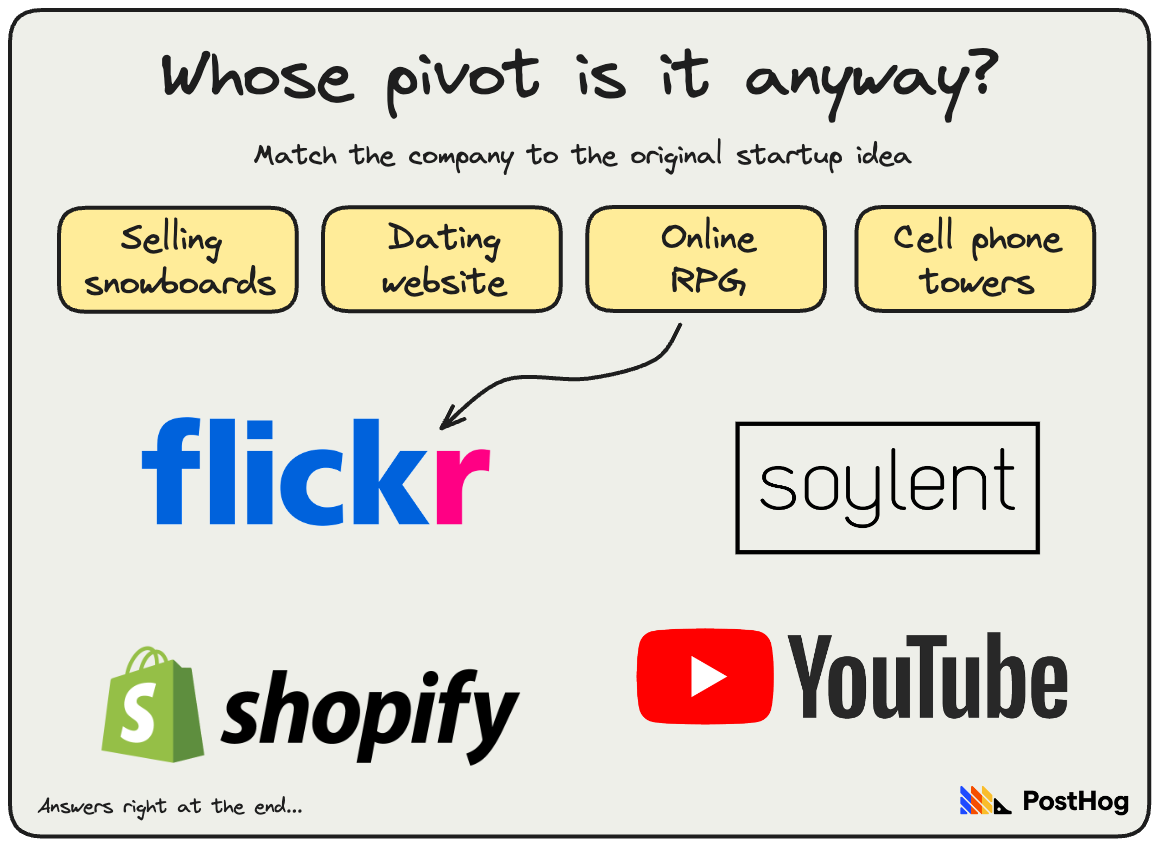

YouTube used to be a dating website. Twitter used to be a podcasting platform. Wrigley, the chewing gum company, originally sold soap. Few startup founders get it right first time, and a well-timed and executed pivot is (almost) always worth it.

Take Wrigley, for example. In the 1890s, when the company started selling scouring soap, packs of chewing gum were an added extra to encourage people to order. But the gum soon proved more popular than the soap. The rest is chewy, minty history.

At PostHog, we’ve pivoted more than most. It took us six pivots (count ‘em) to land on product-market fit. Two years later, we’re speeding past 100,000 users.

This week’s theme is: How, and when, to pivot your startup.

This article was first published in our newsletter, Product for Engineers. It's all about helping engineers and founders build better products by learning product skills. Subscribe here.

1. If you’re going to pivot, make it big

Stewart Butterfield pivoted before it was cool. Flickr, his first big success, was pulled from the wreckage of Game Neverending. The game failed, but the built in photo-sharing feature had promise. Yahoo acquired Flickr for around $22 million in 2005.

After a few years at Yahoo, Butterfield tried to make his game idea a success again. It failed. Again. When it did, he and his colleagues switched focus to the internal communications system they’d built while developing the game. They called it Slack.

In both cases, Butterfield found success by making huge pivots away from his original idea. As LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman says, startup founders can pivot from failure to success, but only if they “slash and burn” the rest of their business.

Why is this important? Pivots should feel scary and uncomfortable. Butterfield could have pivoted to different games based on the same tech, but he correctly realized Flickr and Slack had more potential. If your pivot looks similar to your last idea, pivot further.

2. Is your product the problem? Or the market?

Monzo founder and YC partner Tom Blomfield has more than a little experience in the art of the pivot.

In January 2011, he was developing Groupay – a bill-splitting service for college friends. Groupay was struggling to attract or retain users when he received a smart piece of advice: stop coding new features and start trying to get new users.

“We got one new user after four of us had been cold-calling for two weeks,” Blomfield told Y Combinator’s Office Hours recently. “We knew it was the time to pivot.”

The pivot was to take the core technology, recurring bank-to-bank payments, and apply it to businesses rather than college students. Today, Groupay is GoCardless, a multi-billion dollar unicorn.

Why is this important? Blomfield’s first idea was focused on a market he knew well (college students), but it was hard to engage and monetize. When he was told to stop coding and focus on finding users, he realized his mistake. The product wasn’t wrong, the market was.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Helping engineers and founders flex their product muscles

We'll share your email with Substack

3. Make sure you’re talking to right people

Finding the right market starts with identifying the right people to talk to.

Speak to founders who have walked a similar path before. Speak to industry insiders with experience guiding startups through pivots. Speak to the people whose problem you’re trying to solve. Read The Mom Test.

No matter who you’re talking to, focus on the following:

- Clearly explain the problem you’re trying to solve

- Ask them if they also recognize the problem

- Find out how big of a problem it is for them

- Ask them how they’ve tried to solve it already

If people are being weirdly polite about your idea, or not giving you specific feedback, then chances are they’re not being honest. Ask open-ended questions. Press for direct answers. Don’t just talk to family and friends.

If you’re confident in your idea and you’re getting confusing feedback, think again about who you’re talking to. If you’re speaking to the right people and they’re telling you the problem isn’t there, or isn’t big enough, pivot.

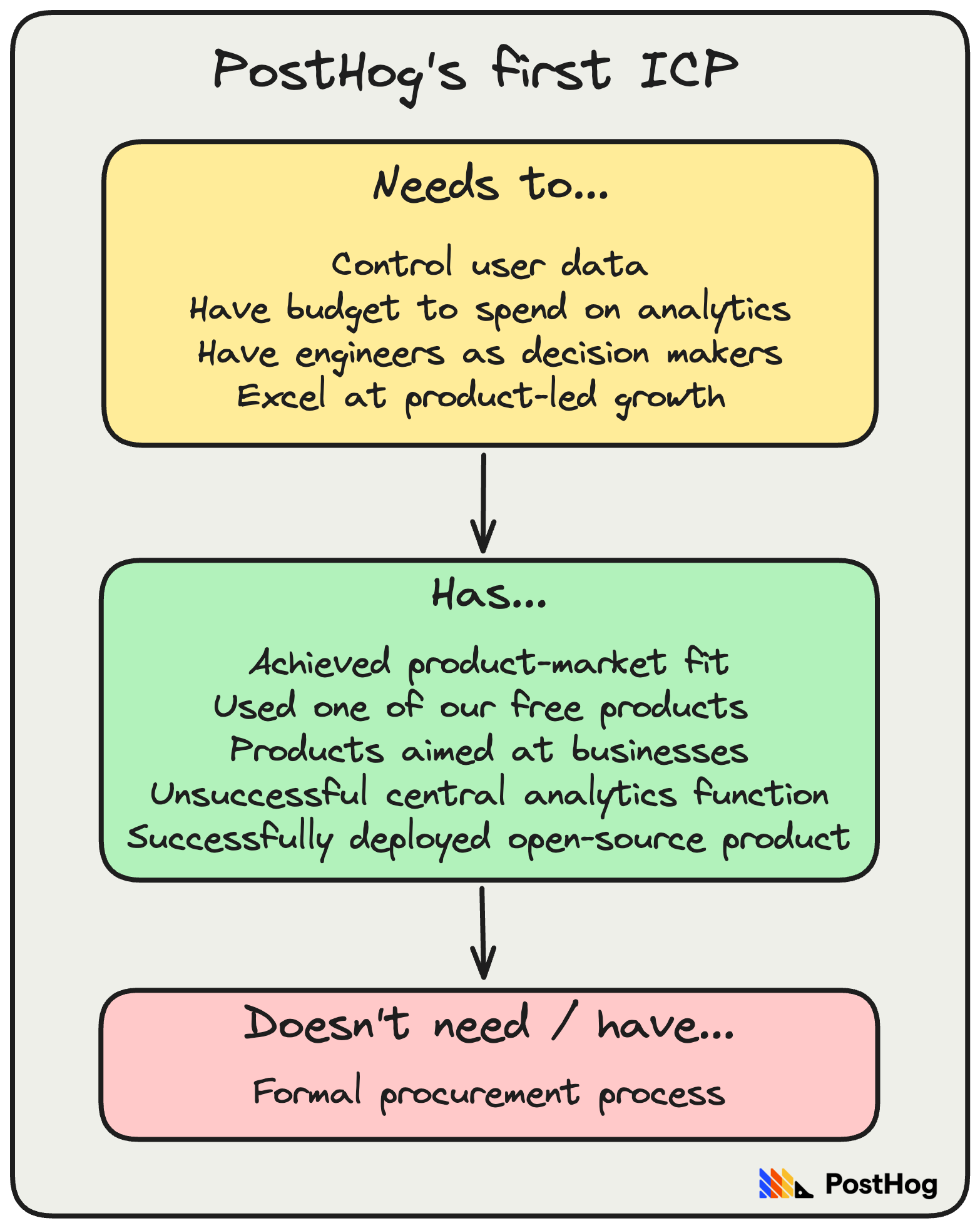

Having a decent theory about your [ideal customer profile[(https://newsletter.posthog.com/p/defining-our-icp-is-the-most-important)], or ICP, will help here. A working hypothesis is enough at this stage. This was ours in the early days:

Why is this important? Speaking to the right people, and asking the right questions, will help you filter the signal from the noise and could help you dodge a mistake that costs you a whole lot of time.

4. Not working on something you’re excited about? Pivot!

Early in PostHog's life, co-founders James and Tim worked on a tool for sales leaders. They hated it.

The problem wasn’t interesting to them. They found dealing with extroverted sales leaders, who feigned interest but didn’t follow through, frustrating. Their idea lacked both founder-product fit and founder-market fit.

So, ask yourself:

- Are you motivated and excited by what you’re building?

- Do you find it interesting to work on?

- Are your current or potential customers desperate for you to succeed?

If you can’t say yes to all three, it’s probably time to pivot.

Why is this important? If you can’t get excited about solving a problem, why should anyone else? As James Hawkins writes in his guide to finding product-market fit: “If you aren't excited about what you're working on, pivot. It's as simple as that. You'll achieve more if you're working on something that feels yours.”

5. Build fast and fail quickly

Talking to people will only get you so far. To really stress-test an idea, you’ve got to build it. “You cannot validate an idea. It doesn’t exist,” says 37signal’s Jason Fried. “You have to build the thing. The market will validate it.”

So build fast and go back to the people and companies you had early meetings with. They told you they had a problem, now you’ve got the solution. Ask them to try it out. If they get stuck or don’t use it much, ask them why. Ask for blunt feedback.

Ask these questions:

- Is the problem you’ve solved high priority?

- Is your solution easy to use or a hassle?

- Is there a big, obvious flaw you’ve missed?

- What works?

- What is it missing?

Don’t fall into the trap of thinking it takes months to build a proof-of-concept – it can be done in a few (very busy) days or weeks.

Why is this important? PostHog pivoted five times in six months before finding the right idea. Each time, we built fast and got real people try things out. Building fast and testing will save you a lot of time - but only if you ask the right people the right questions.

6. Be decisive

Sleeping on something is a good idea; sleeping on it for a week isn't.

Be honest with yourself: how much time do you need to think something through before making a big decision?

Define that timeframe and stick to it.

Good reads for product engineers 📖

The Big Pivot Podcast – Stewart Butterfield: Find 37 minutes in your day to listen to Slack co-founder and CEO Stewart Butterfield in conversation with Reid Hoffman on how to navigate big pivots.

Enterprise is Dead – David Cramer: Sentry’s co-founder and CEO on why “the era of servicing only the Fortune 500” has been killed by Sentry’s target market, the Fortune 500,000.

Why software projects fail – Vadim Kravchenko: Vadim outlines how overconfident engineers, inexperienced managers, and mismanaged stakeholders can derail promising projects.

How startups beat incumbents – Jason Cohen: An in-depth guide from the founder of WP Engine.

Answers. Snowboarding: Shopify. Dating website: YouTube. Online RPG: Flickr. Cell phone towers: Soylent.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Helping engineers and founders flex their product muscles

We'll share your email with Substack